business Articles

I write in-depth articles about all sorts of things, from science and technology, to business and art, to history and the future. For articles I have contributed to and interviews with me, please see Press & Interviews.

Read my features in TIME Magazine’s Special Issue on Artificial Intelligence on newsstands until Mid-March!

A User’s Guide to Generative AI

At Nearly 70, AI Comes of Age

Video and Audio Writing

Science and Futurism with Isaac Arthur

Mobile Cities

Humanity has often preferred to move its communities, and in the future we might do that by moving our entire cities, by air, sea, or land.

Forgeworlds & Industrial Planets

The industrial revolution saw the rise of factories so big they often grew entire towns or cities around them to operate, but in the future entire planets might be used to fuel the titanic projects for conquering the stars themselves.

I’ve also edited the scripts for many more SFIA episodes. Here are some of my favorites.

Be Smart - PBS

The Science of Dreams

It would be a lot easier to study the science of dreaming if we weren’t asleep every time we did it. Why do we dream? What does dreaming do for our brains? How did dreaming evolve? Here’s a look at the current theories from psychology and neuroscience.

Curiosity Daily Podcast - Discovery

I’ve written over 50 segments on science for Discovery’s Curiosity Daily. Here are a few of my favorite episodes:

TED Ed

Cover Stories and Feature Articles

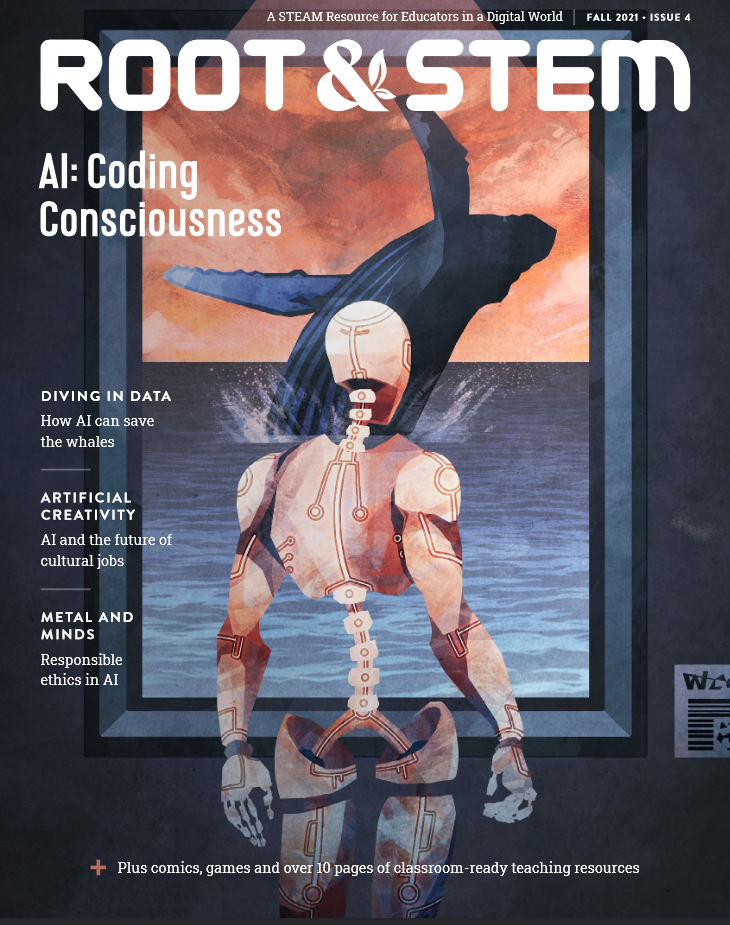

Artificial Creativity: AI the the future of cultural jobs

As far back as human memory stretches, we have worked side by side with animals. Whether it’s a shepherd whistling complex directives to her sheepdog or a cowboy at one with his horse, there’s a human competency that allows us to empathize with minds and hearts vastly different from our own and align ourselves toward a common goal.

In the future, creative professionals who rely on AI to co-create their art might experience something similar. A lot of the human contribution in AI art comes from the dataset they choose to feed their AI collaborator. That training set defines a large part of the output. They can also set the initial parameters of what they want to see and often have an intention or direction in mind and a rough idea of what the computer might come back with.

But once the network starts churning out options, the creative process becomes much more of a dance, a kind of two-way banter between human and machine.

Yuval Noah Harari and Fei-Fei Li on Artificial Intelligence: Four Questions that Impact All of Us

More questions than answers were generated during a recent conversation at Stanford University between a pair of Artificial Intelligence giants — Yuval Noah Harari and Fei-Fei Li. Nicholas Thompson, editor in chief of WIRED, moderated the 90-minute conversation in the packed Memorial Auditorium, filled to its 1705-seat capacity.

The purpose was to discuss how AI will affect our future.

Natural Language Processing: The Essentials for Customer Experience

“Hey Siri, what’s natural language processing?”

She hears me perfectly, and after less than a second she pulls up a Wikipedia article on Natural Language Processing. I skim it. It tells me that Natural Language Processing, usually abbreviated NLP, tells us how to program computers to process and analyze large amounts of natural language data. Yes, Siri, if only it were that easy.

The new look of analytics: Six trends to watch for

As we’re sparring, my kickboxing trainer asks me the same question in every session: “Where are you looking?” While I am supposed to be looking broadly at the various places that a punch or kick could come from, noticing and taking advantage of potentially beneficial openings, I am almost always focusing on the task immediately at hand – avoiding that fist coming right towards my face.

Often, it’s the same at the office where there are myriad daily distractions. While switching focus from project to project, it’s rare to find the time to look more broadly at trends in industry as a whole and to notice the similarities in the problems faced by many businesses. But, major changes in consumer and business behaviour are becoming more and more evident across sectors. These changes give an indication of how the relevance and demand for certain specialized analytics may rise, thereby shaping the new look of analytics.

The social butterfly effect: Tips on measuring crucial social factors in new product research

There was something extraordinary about shopping for a smartphone on June 29, 2007. There was no choice-based-conjoint-style side-by-side comparison of different devices. Shoppers didn’t need to be convinced that the switch from their existing device was worthwhile. A list of product specs that let customers assess whether the new smartphone’s features would fulfill their needs was nowhere to be seen. No customer decided that the posted price was too high.

Instead, the experience of buying the first iPhone was an intensely social one. Shoppers who had been lining up for days – some of them for weeks – shared an important cultural experience. Their decision was reinforced by their peers: “The first shoppers to emerge victorious were cheered as heroes and brandished their trophies for the cameras.”1 The product itself was dubbed the “Jesus phone”2 and its launch was billed as “revolutionary” from the company’s very first press release.3 Rather than being a solo undertaking, the purchase experience took on new dimensions, with a myriad of psychological, cultural and social components.

Getting more mileage out of your segmentation

Clients love the insights provided by segmentation in understanding the variety of customer needs, informing communications strategies, and its practical application in encouraging behavioural shifts.

So why does their usefulness often seem to disappear once a strategy is implemented?

Different tactics are needed to make a segmentation analysis useful for the long term because the client's success in acting on the recommendations of the initial study will affect the future research potential. If the recommendation of the research is to target a specific segment, the characteristics of those individuals may change, creating a feedback look from the research results to the research recommendations. Understanding how the characteristics of the segments are impacted by targeting the typologies is the key to carrying the research into the future.

Pricing innovations: Strategies for launching new products

Revolutionary products are easy to name: the Xerox photocopier, the Apple iPod, Facebook.... Many companies aspire to launching new blockbuster products because the payoff can be enormous. However, developing and marketing an innovation is a significant risk, since predicting whether a certain offering will succeed or fail is extremely difficult. Concept testing is a nuanced art in which good marketing research can play a key role.

Much empirical and theoretical research as gone into explaining how new products are adopted by consumers and the underlying reasons for adoption. A firm that can take into account the dynamics of adoption has a much better chance of launching a successful product that the firm that does not bear such dynamics in mind. What's more, the firm has something at its disposal that can help it directly influence the adoption of its new product: the price it charges. Developing a pricing strategy can help the firm maximize the benefit from its new innovation.

Are surveys supposed to be fun?

The jig is up: Respondents know we ask them to do surveys. They know that someone is telling someone else what percentage of people saw a business's ad and linked it to the right brand, predicting how many people might try a new product, or deciding which creative execution people liked better. In other words, surveys are obvious in their collection of opinions. Both researchers and respondents know that we are asking these questions because we want to know the answer: surveys have a purpose.

Games, on the other hand, are designed to be, well, games. They are created to be enjoyable or challenging, but they are not usually designed to be useful.

So far, the conflicting functions of survey research and games have been given little thought, as researchers have attempted to use gameful design principles to augment their survey research.

But what does this opposition of purpose mean for gamification of survey research? As it turns out, it might mean a lot.